The Power Law vs. The Long Tail (Part 1)

How “Swing for the Fences” Thinking Can Limit Funds’ Performance, and What to Do Instead

PART 1: The VC Power Law: Siren Song of the Unicorn

The venture capital ecosystem thinks and operates like no other part of the finance and investment world. While its notional cousin, private equity, typically seeks to invest capital and resources to create compelling returns with consistency and a very high success rate, venture capital funds rely on the pursuit of a spectacular return in a tiny minority of portfolio investments, typically only one, to offset poor to catastrophic performance in the dozens or sometimes even hundreds of other investments in the fund. This notion, the "VC power law" (an interpretation, popularized by Peter Thiel and others) of the statistical axiom of the similar name), began as an observation of the performance of the most storied early venture funds and is now treated as a guiding principle for how funds should structure their investment and strategy.

In this and a few upcoming short articles, I'll discuss the fantasy versus the reality of the VC power law, and also the alternative approach, attending to the "long tail" of a portfolio, and why that new approach makes so much more sense for the VC ecosystem as it has evolved in the last decade or so. In short, continuing to do things the old way isn't going to be merely less fruitful; it could do serious damage to venture capital as the bastion of the financial ecosystem that is largely responsible for driving all types of innovation.

The retrospective observation of how a handful of super-performing unicorns has "made" the reputation of some of the most storied names in venture capital has led to the fantasy conclusion that doing things the way they did is sure to yield the same results (perhaps this was heightened by the tendency for modern social media and publications to extol the fables of Uber, Airbnb, Amazon, Google, etc., while scarcely uttering a word for the many hundreds of others that failed trying to do essentially the same things.) The inconvenient reality here is that even for the largest, most well-resourced funds, it often occurs that nothing in the portfolio turns out to be the kind of Grand Slam that offsets the sub-par performance of the rest of the portfolio.

In a forthcoming article, I'll talk about how the trend, really an explosion, of micro funds exacerbates the problem with attending only to VC power law ideals, by creating an ecosystem that is dominated by funds with insufficient resources to make more than a relatively small number of investments (barely diversified, and not nearly enough to assure unicorn-tinged victory), much less the capacity to support the portfolio and help more winners emerge at any level. From there, we'll look at the alternative approach (ironically tried and true in an adjacent zone of the financial ecosystem, private equity) that I believe has a far better likelihood of resulting in superior-performing portfolios for this new breed of smaller-sized (and staffed) funds.

Large established funds have the resources to be able to screen and vet a large number of investments, perhaps 50 or more for a given fund (and hundreds across multiple fund vintages), and to provide basic governance support (i.e., board presence) for the portfolio. The typical micro-VC fund on the other hand has limited resources for vetting and selecting its investments (not to mention negotiating favorable terms amidst all the other VC competition), and even more so for the ongoing curation and support of their portfolio. The net result is that most small funds really cannot make more than 10 to 15 investments with any real diligence or ability to provide the level of engagement that will boost those investments' chances.

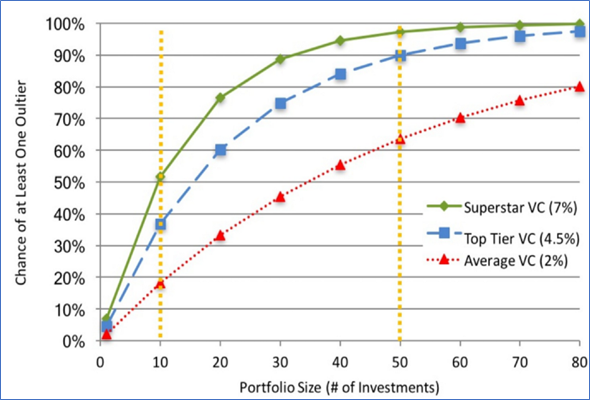

Now look at the chart below, showing the probability of an outlier in portfolios of various sizes and for three different levels of fund performance. This chart is based on retrospective data from Cambridge Analytics and Horsley Bridge (Source: Picking winners is a myth, but the PowerLaw is not).

● Average VC (red dashed line) has a 2% chance of an outlier with every investment. This based on reducing the Cambridge Associates industry average of 2.5% a bit to remove top tier Investors.

● Top Tier VC (blue dashed line) has a 4.5% chance of an outlier success with every investment. This based on the Horsley Bridge data.

● Hypothetical Super Star VC (green solid line) has a 7% chance of an outlier success with every investment. This hypothetical VC is 50% better than the top tier and is useful in testing the "I can pick winners" assertion given by firms with concentrated portfolios.

There's a lot to unpack in the chart, but a key observation relates to the reality that small funds with relatively tight resources will tend to be limited to making a smaller number of portfolio investments, closer to the left hand yellow vertical line, compared to larger and better-resourced funds who can make far more, closer to the right-hand yellow line. A typical micro-VC might have the resources to make perhaps 10-15 or so well-considered investments, which on average still gives them less than a one in three chance of scoring a Unicorn outlier, and only around 50% even if they do a far better than average selection job like the top tier funds. Look at the statistical distribution in the article, and what really stands out is the improbability of most funds, especially small ones having even a single superstar outlier in their portfolio.

Keep in mind that deal flow quality, deep diligence and ongoing curation and support is what differentiate the average funds from the top-tier and superstar ones. Certainly, a micro-fund short on resources but hoping to get some benefits from diversification can make a larger number of investments with relatively less deep diligence for each, but this semi-random approach pretty much assures that the fund's performance will tend towards the average, not the pantheon – unless of course, that fund has the rare ability to perform deep diligence far more efficiently than most, but we'll talk more about that in another article.

The unfortunate thing about the VC power law is that it can lead to a behavioral phenomenon that is one of the Dirty Little Secrets of the venture capital world: concentrating attention on those companies swinging for the fences, which often has the corollary effect of not paying enough attention to the rest of the portfolio companies if none of the others seem on the path to stratospheric greatness. This deficit of attention to those companies naturally further reduces their probability of performing well. Many funds essentially write off most of their portfolio entirely to concentrate their energy, resources, and capital on the potential unicorn rockstar they are hoping will "make" the fund. (This can take many forms, from reduced oversight and engagement, as in turning over board involvement to junior team members, to opting out of subsequent investment, etc.).

But treating a portfolio like that is a bit like planting a garden full of seeds, and then only watering and fertilizing the first ones that sprout. now look again at that chart and its statistics. if you apply the VC power law’s behavioral effect of attending slavishly to that hoped-for unicorn at the expense of the others, then as a VC you are signaling to your savvier LPs that top-tier performance of your fund is less likely than winning a flip of a coin.

In contrast to the VC power law, there is the notion of the "long tail" in portfolio management. This refers to the fact that many companies in a portfolio, while not necessarily making it to the stars, might very well yield respectable results with confidence and strong, experience-based support from their backers. In other words, in a given portfolio, there might only be zero or one unicorn outliers, but a sizable fraction of the rest would still deliver a significant positive return to investors if they are given a chance to do so.

Getting that chance in the world of early-stage startups means receiving adequate operational, network, governance, not just capital support.

In the next installment in this series, I'll dive into what the long tail in a VC portfolio could look like in terms of company characteristics, needs, opportunities and risks, and what enlightened stewardship of that portfolio can look like within different fund sizes and shapes. I'll also take a look at the typical natural construction and characteristics of a new small fund run by emerging managers (something I know all too well from personal experience and observation). As it happens, if done with the right mindset, approach and focus, there is a match made in heaven between the two; and there is also a Faustian bargain to be avoided resulting from micro-VCs too slavishly following the siren song of the VC power law. It should come as no surprise that the “secret sauce” is network, and a kind of leverage and collaboration with partners aimed at bringing the right resources into the mix, in the right measure and at the right times, without wasted overhead.

In the next part of this series, I’ll look at how the new micro-VC fund managers can level up by acting less like gamblers and more like farmers.

#venturecapital #startups #entrepreneurship #VCfunds #portfoliostrategy #unicorns #financialanalysis #diversification #riskmanagement #investment #powerlaw #startupfunding #entrepreneurship #portfoliotheory #investmentstrategy #microVC #VCevolved #emergingfunds #emergingmanagers #impactVC #privateequity #familyoffice

Credits: Photo by Brandon Morgan on Unsplash